Difficulty at the Beginning

I.

At the start of summer 2022, all I wanted to do was quit my well-paying product design job and take up singing lessons. I’d never had a passion (or talent) for singing, so it made no rational sense why I should suddenly want nothing more than this.

At the time, I worked at an eLearning and coaching startup. I was conducting research by evaluating user experiences of different learning platforms — particularly one that Microsoft had recently acquired: TakeLessons. I signed up to look around and came across vocal coaches on the platform.

One of them stood out to me because earlier that day, I’d met my new neighbor who shared her name (I’ll name them here as Fran). I felt a subtle nudge to book a lesson with her that I reasoned could be part of the research. But I didn’t go through with it because her rates seemed too steep for someone with no singing background or any future aspirations related to it (other than a short-lived bout of wanting to get into voice-acting a few years ago).

Besides, I was already struggling enough just getting through my day without adding another activity to it.

A few weeks earlier, I’d recognized that I was severely burnt out, and it wasn’t confined to just one sphere of my life. Personally and professionally, physically, mentally, and — worst of all, I’d thought — creatively.

Deciding there was no recourse other than to leave the — understandably scrappy but ill-suited for my condition — early-stage startup environment, I’d negotiated an exit with the company some weeks out with only one plan: recover.

And the strategy for this plan? No idea. Maybe just take some time to rest. Maybe take some time to travel. That’s what people do, right?

The next morning, I ran out of honey. I started each morning with a little honey before breakfast as part of my routine for years. So I wrote a note: “Make sure to get honey today.” That morning, my parents stopped by my apartment to drop off a box of some old things I’d left at their house. One of these items was a microphone I’d bought during my aspiring voice-acting phase and hadn’t seen in years.

Later in the day as I was making lunch, I heard my new neighbor, Fran, singing loudly. When I went back to my desk, I saw I’d received a welcome email from TakeLessons with a code for three discounted lessons with any instructor. I looked Fran up again and dug a little deeper. Her studio’s logo was a honeybee.

On another day, I may not have made any connection between my running out of honey and Fran’s logo or considered my neighbor’s loud singing as anything other than a nuisance. But these were too many coincidences in close temporal proximity and I understood — on some deep, subconscious level — these events were significant. So I signed up for three lessons with Fran.

Carl Jung called these meaningful occurrences “synchronicities” — external events that coincide with an internal experience (a thought, a dream, or a feeling). Without any traditional or temporal sense of cause and effect, they only seem to be connected by personal significance.

Jung described synchronicities as symbols of collective human archetypes that drive behavior and perception, and believed they indicated underlying connections between individuals and larger patterns of the world — hinting at a hidden order to a seemingly chaotic universe.

In a simpler sense, I prefer to think of synchronicities as cosmic affordances. An “affordance” in design and cognitive psychology refers to a property of an object that suggests how it can be used. For example, a door’s handle “affords” pulling to open a passage.

Cosmic affordances, then, are intuitively deduced cues from the universe that suggest a path of action leading to a desired outcome.

After my first lesson with Fran, it became clear that our journey wasn’t really about singing. While we focused on vocal techniques, Fran’s intensely authentic and contagiously motivating energy revealed a deeper purpose: reclaiming my full self. She helped me recognize how societal and cultural conditioning had suppressed my voice, literally and metaphorically, and stifled my true expression.

My burnout wasn’t a sudden collapse; it was the cumulative effect of years spent masking myself under the layers of repressive programming that had kept me from voicing what I truly wanted, personally and professionally.

Fran also helped dispel my fears around judgment and getting out of my comfort zone by assigning mortifying tasks like recording myself singing and sharing those recordings with people I knew to get their reactions.

After three lessons, I told her I needed to pause our sessions. Without a reliable income for the foreseeable future, I wasn’t sure if I should continue. Out of curiosity, she asked what I did for work and when I mentioned UX, she lit up and said, “I need some help with my site!”

That cosmic algorithm came through again. We agreed on a barter: in exchange for actionable design feedback, I’d receive more lessons.

*

As part of my plan to recoup, refresh, and restart, I’d booked a trip to the Scottish Highlands for a bit of soul-searching (originally having come from South Asia, where else might I possibly go to “find myself”?). But my dates coincided with my sister’s time off from work, and suddenly my parents had never had any dreams other than visiting the Isle of Skye.

What was supposed to be my life-altering solo adventure morphed into a family vacation — one that indicated the usual blend of strained conversation and petty disagreements paired with mild enjoyment.

The upside was that my dad was comfortable driving around the UK, which meant we could rent a car and explore the country at our own pace rather than being tied to pre-booked tours and rigid train schedules.

Uplifted by the thought of leisurely drives along lochs, castles, peaks and glens, I surrendered to the new itinerary and planned a road trip instead: a few days in Edinburgh, then off to the Highlands and Skye.

On our second morning in Edinburgh, I woke up before my family, left them a note, and slipped out to a café around the corner for a quiet breakfast alone. The café had just opened, so I found a cozy corner window and settled in, savoring my solitude with a cup of Earl Grey and a view of Arthur’s Seat through the morning rain.

The place quickly filled up with university students, but I remained undisturbed in my corner until a woman, about my age with black hair and an American accent, asked if she could share my table for a bit. After hearing my equally American-accented response, she struck up a conversation.

She was a student at the University of Edinburgh, originally from upstate New York. Having spent a third of my life in New York City, we freely swapped stories over tea and toast. Throughout our conversation, I sensed something oddly familiar about her — like I was catching up with an old friend rather than meeting a stranger for the first time.

We talked about my plans in Edinburgh and I asked her for recommendations. After offering the usual tourist suggestions, she mentioned a fire dancing class she’d signed up for that evening and shared the details. This was unexpected and just a bit further outside my comfort zone than I was willing to venture. I hesitated to share in her enthusiasm but thanked her nonetheless.

As we gathered our things to leave, she said, “You look like my friend’s sister-in-law. This whole time, it felt like I’d seen you before. I just realized that’s who you remind me of.”

With a parting smile, she mentioned that her friend — also American, from Texas — would be joining her that night, and said she hoped to see me there.

The cosmic algorithm confirming our mutual sense of familiarity nudged me to explore the synchronistic opportunity. Ignoring the list of potential hazards and gruesome injuries my mind kept cycling through, I signed up for a fire-spinning session with a teacher named Iga.

Not wanting to invite fears or concerns, I kept my plans to myself that day. After a late afternoon trek to Calton Hill, I told my family I needed a solo walk in Meadows Park and promised to meet them for a late dinner.

I met Iga and the girls on Candlemaker Row and we walked to the park together. It was just the four of us that night.

Following a brief (too brief, if you asked my nerves) safety demonstration, Iga handed us the sticks we’d be using, which were soon lit on both ends. We followed her movements as she guided us through the steps, spinning amid flames. My apprehension quickly faded as our cautious steps nimbly turned into a mesmerizing rhythm. Flowing with the fire, it was impossible to be aware of anything other than the present moment. That’s how we spent the next hour, immersed in the radiant bloom, reigniting each other’s flames whenever one went out.

What I remember most is the sound of the fire rippling through the air around me — a kind of primal reassurance — a Promethean spark — for the time to come.

Under the moon in the Meadows, I learned to dance with fire.

Whether it was the drive through serene landscapes and forests on rainy days, the fresh mountain air, the near-supernatural atmosphere of Skye, or the true start of fall (we were there in early October), the rest of our trip put us all in a contemplative mood.

And just as my night away in Edinburgh had hinted, I found the adventures I’d sought, even if they unfolded differently than I expected. I climbed the hills and mountains the others refused to take on, whispered my wishes to tiny rocks tossed into faerie pools, saw what the dinosaurs left behind at An Corran, and fed Highland cows.

The inner sanctuary Scotland had offered was, however, only a brief respite. When I returned to D.C., my external circumstances awaited me, unchanged.

*

Three months into what I optimistically called “rest,” I tentatively started looking at job listings — mostly to figure out what type of role might suit me next. But as soon as I stepped back into interviewing, it became clear I wasn’t ready.

For a few years now, Design had become a cycle of resigned frustration. I did the work I was tasked with, and I did it well, but it had become a joyless process of ticked boxes and formulaic accomplishment.

And it wasn’t just dampened creativity. Burnout and exhaustion had locked me into survival mode, affecting every aspect of my routine. Everything was just about getting through the day. But the prospect of a complete foundational reset was daunting, and with several months already gone since leaving my last job, I felt a growing pressure.

This gap reminded me of a time once before when design had lost a bit of its luster for me. After my second year at Parsons School of Design, the only financially viable path in my field seemed to be going into advertising — something I couldn’t even be paid to consider. Unable to justify the cost of design school without a clear plan, I took a year off to reassess.

Despite my efforts, nothing else appealed to me and I returned to Parsons on a gut feeling. As a late-returning student, I could only register for classes a week before the semester began, and the only elective left with an open spot in my program was a brand new class called Information Architecture, taught by Abby Covert.

At the time, I barely knew what UX was — this class was Parsons’ first inclusion of it in the curriculum. But from the moment that class began, everything clicked into place. Abby’s clear and purposeful approach, focused on “how to make sense of any mess,” helped me find a sense of direction again. This was why I’d come back. To learn how to create simplicity out of chaos.

I took every UX course offered after that, grateful that my introduction was guided by someone so devoted to their discipline. If I hadn’t taken that year off and returned on that gut feeling, I might have missed out on the one class that reconnected me with design.

But back in the present, I was stuck, attempting to freshen up my portfolio while knowing deep down that what I actually needed was to take a real break and make sense of my current mess. But how would I sustain such a long break?

The universe decided to chime in. That week, construction began on a new building right behind mine, with sounds of whirring drills and jackhammers echoing all day. On top of that, I also had to decide whether to renew my lease with an extortionate rent hike. As I was already not-really-deliberating, my dad called, and once he heard the construction noise in the background, invited me to stay at their house until it was all over.

It wasn’t hard to deduce what logic and intuition were both pointing to. The world around me was reflecting my next steps with startling clarity.

And so, brimming with uncertainty and doubt yet propelled by undeniable cosmic momentum, I gave up my apartment and moved in with my parents to take an as-long-as-it-takes break to rebuild, restructure, and reconnect with my creativity.

Explaining this decision to my parents was challenging. They struggled to understand the need for my “nonsensical” plan to take an indefinite break from work.

(“Your sister has worked 24-hour calls in the ER. If she has never burned out, how can you?”

“Well, there’s a simple reason: we’re two different people with different abilities, experiences, and functional capacities.”)

Using my newfound vocal confidence, I (eventually) negotiated the time, space, and quiet I needed to start my recovery process. And my parents’ criticism became a useful constraint that pushed me to cultivate deeper self-trust and belief in my decision. No external crutches — except, of course, the entire universe offering guidance at just the right time.

•

II.

In the introduction to his book Design for the Real World, Victor Papanek defined design as “a conscious effort to impose meaningful order.” With this definition, he suggested that any planned and patterned act could constitute a design process: “composing an epic poem… reorganizing a desk drawer… baking an apple pie… educating a child.” Or, in my case, recovering from creative burnout.

Drawing on the principles and processes I learned in my design education and from my experience as a product designer, I set out to create a framework for creative transformation.

Guided by cosmic affordances, I would rebuild a foundation for my life with desired habits, behaviors, and thought patterns, creating a stable base for reconnecting with and sustaining my creativity.

FRAMEWORK CONSTRAINTS

In devising my framework, I had to work within two primary constraints:

Limited Financial Resources: While I understood that recovery would take time, the lack of knowing how long it would take required that any investment be essential and economical.

No Completely New Routines: Previous attempts at implementing entirely new routines for a holistic restructure had consistently failed to stick.

Rather than viewing these as limitations, I reframed them as guiding constraints. The financial constraint became an asset in my self-experiment, compelling me to rely solely on intuitive understanding and personal knowledge to craft a recovery path contextualized in my circumstances, rather than forcing a prescribed approach through therapy or coaching.

The second constraint directly informed the structure of a process-formula I developed for creative transformation, forming a bridge between a current, undesired state and a desired state for any habit.

Through this reframing, these guiding constraints made my framework sustainable, flexible, and reusable.

MIND-INTELLIGENCE AND BODY-INTELLIGENCE

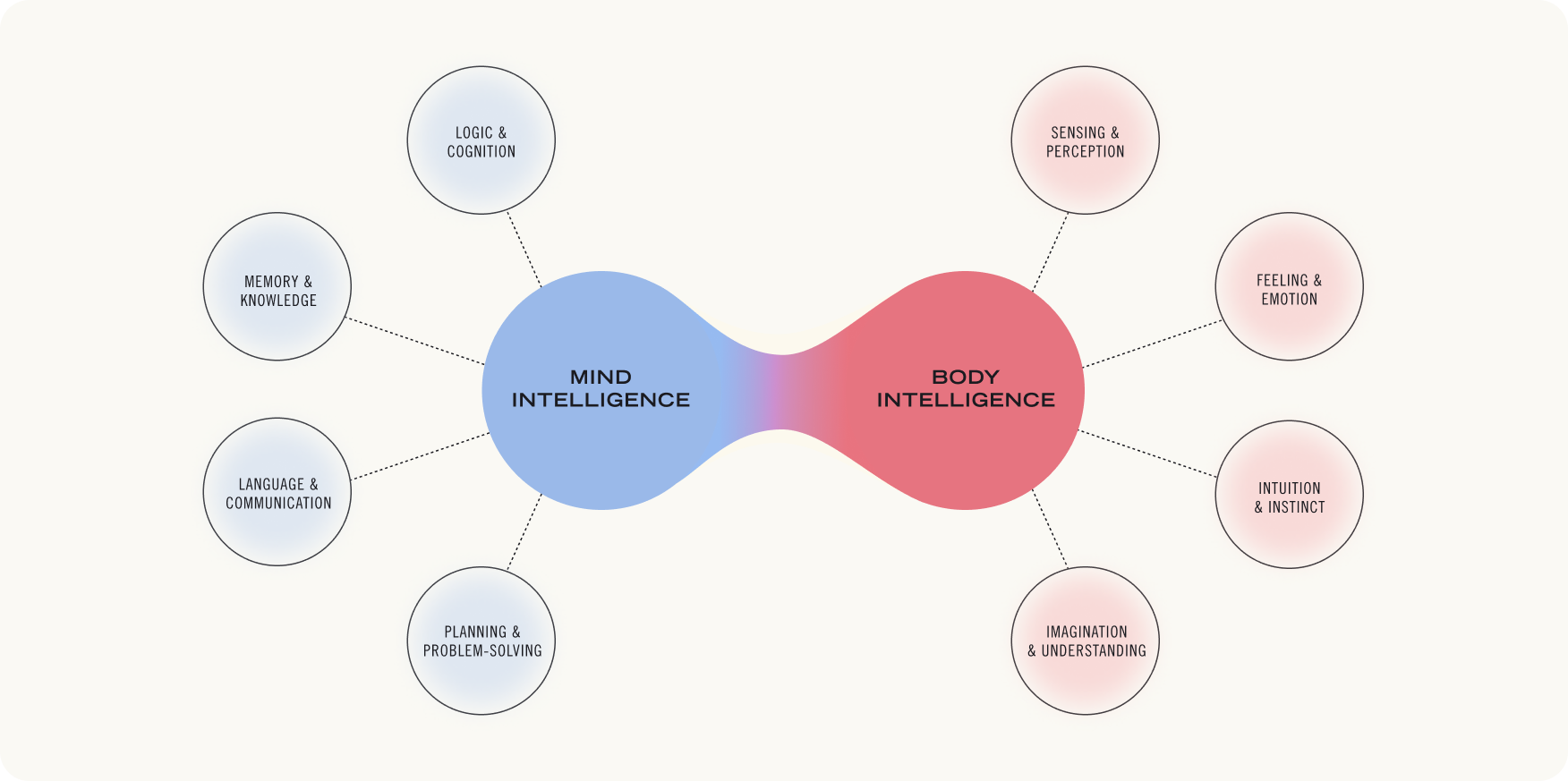

I’d noticed that when I recognized a cosmic affordance, the understanding of its personal significance was registered in my body first; it was a gut feeling. To define my system, it was important to distinguish between the faculties of mind-intelligence and body-intelligence.

Mind-intelligence operates through the lens of logic and analytical thought. It’s the realm where knowledge is stored, patterns are recognized, and language is used to articulate ideas. This intelligence draws on reasoning, memory, and sequential processing to make sense of the world.

When planning a project, for example, mind-intelligence breaks down the tasks, schedules timelines, and tracks progress, ensuring that every detail is considered and executed with precision.

Body-intelligence, on the other hand, is where intuition and understanding reside. It’s a subtler, more fluid intelligence that senses, feels, and emotes — processing information in a way that’s often beyond words. This intelligence perceives significance through gut feelings, emotional responses, and embodied awareness. It’s where creative impulses originate.

For instance, when we meet someone new and immediately feel a strong connection or sense of trust, that’s body-intelligence at work, guiding us through an unspoken, instinctual understanding of the situation.

In my framework, I recognized cosmic affordances through intuitive resonance: a gut instinct or hunch sensed by body-intelligence as understanding through feeling, then translated by mind-intelligence as knowing through language and pattern recognition.

This formed the core of my decision-making process so that both analytical reasoning and embodied understanding guided my path.

AUTHENTICITY VS. IMITATION

Another key distinction was the difference between the authentic and the mimetic. To reconnect with my creativity, authenticity in words and behaviors was essential because a creative path is inherently an authentic one.

The financial constraint proved particularly helpful here because it steered me away from any off-the-shelf, ready-made solutions that could’ve turned my developmental path into a replica of someone else’s methods. Instead, solutions would emerge naturally — recognized by my body-intelligence and implemented into practice by my mind-intelligence.

To precisely articulate this delineation: an external event, object, or person may inspire, influence, or catalyze a step along my own path (this signifies the cosmic affordance), but they may not define the path — that’s the realm of imitation. Authenticity in this context meant that while I might draw from various sources, the final direction I take would be guided by my inner compass, not dictated by any external template.

(This piece on Batesian mimicry inspired the codification of this distinction in my system. “Who can best tell the difference between a Coral Snake and its Mimics? The Coral Snake itself.”)

CONTAINERS FOR CREATIVE TRANSFORMATION

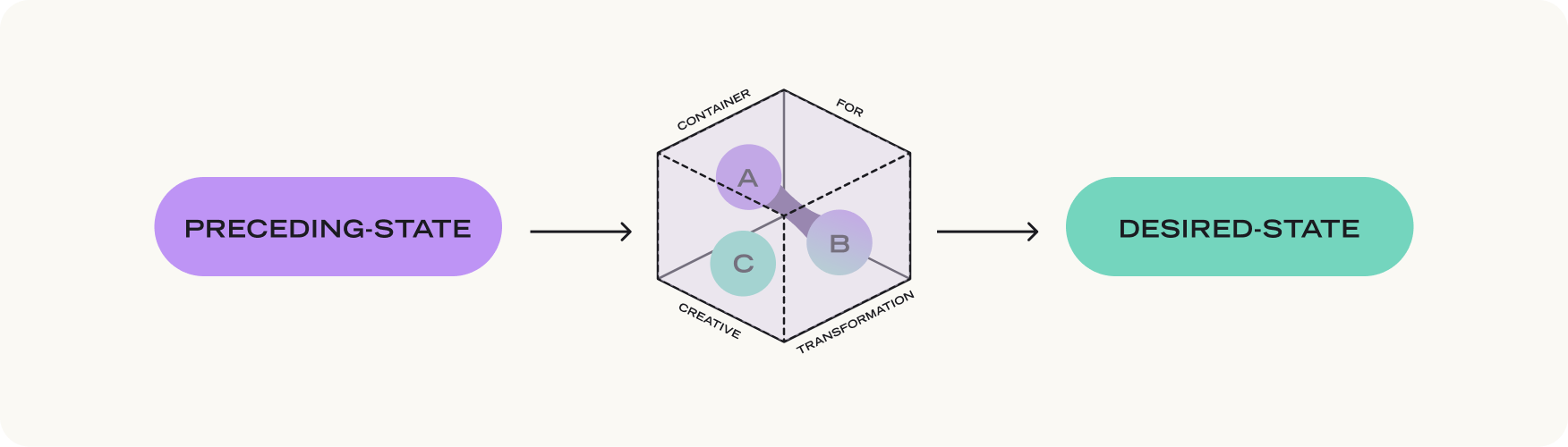

To create sustainable and manageable shifts in habits or patterns, I developed a versatile process-formula that was universally applicable across all habits and patterns — transitioning from a preceding-state to a desired-state.

Referencing the second guiding constraint, the process-formula emphasized individualized habit adjustments over a comprehensive routine overhaul, which could be difficult to sustain. This approach ensured that when I occasionally, inevitably, humanly, reverted to a preceding-state, I could use the specific, bite-sized formula to return to the desired-state without needing to realign the entire routine.

To guide the development, I drew inspiration from the design process and principles I applied to a platform redesign project at the coaching startup. The essence of the process was to retain what worked, modify what could be improved, and introduce new features to create an adaptive, desired experience.

I termed the intermediate phase (bridge-state) of the formula a container for creative transformation. Within this container, a combination of conditions catalyzed the shift from preceding-state → desired-state.

The Conditions:

A condition from preceding-state that is recognized and addressed (condition A);

One modified condition derived from preceding-state (condition B);

One new condition introduced to facilitate shift (condition C).

Integrating Condition A into the transformation container acknowledged that every change begins with a clear understanding of our current state. It’s not just about discarding what no longer works, but recognizing its role and adapting it for new purposes.

With this formula in place, I had assembled the components of my transformation framework.

FRAMEWORK FOR CREATIVE TRANSFORMATION

Observation of Undesired-State: Either mind-intelligence or body-intelligence notices an undesired-state, setting the foundation for intentional change.

Commitment to an Intention: Once the undesired-state is identified, an intention is set to transform it. This intention acts as a guide for the subsequent steps, focusing efforts on a specific goal. Demonstrated commitment to the desire for change creates space for a cosmic affordance to emerge.

Observation of Cosmic Affordance: The change process is catalyzed by detecting a cosmic affordance through intuitive resonance.

Body-intelligence understands the personal significance of the cosmic affordance through sensing, feeling, and emoting.

Definition of Conditions for Process-Formula: Once a cosmic affordance is understood, its guidance is applied within the container for creative transformation.

Mind-intelligence interprets body-intelligence’s understanding into actionable knowledge through pattern recognition, logic, and language, and defines the practical conditions for the creative transformation process-formula.

Sustained Practice and Emergence of Desired-State: With continued adherence to the set conditions, the desired-state gradually emerges, replacing the undesired-state with new patterns of thought and behavior that reflect the initial intention.

Feedback and Adjustment: Regular assessment and any necessary adjustments to the transformation process keep it responsive to new insights and changing circumstances. An iterative approach emphasizes that transformation is an ongoing process that requires flexibility and adaptability.

TRAINING INTUITION

Cosmic affordances would not be demanded. They are ineffable, empyrean workings of the matrix — a law only unto nature itself. And nature functions with uncalculated efficiency. It doesn’t require our meddling. “Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished,” as Lao Tzu observed.

Traditional logic might suggest that increasing the level of social interaction would lead to a greater likelihood of encountering personally significant events. However, I found the opposite to be true. More social engagement often introduced greater external interference, complicating my ability to discern genuine synchronicities.

It also heightened the temptation to force meanings out of impatience and frustration, which dulled the connection with my own intuition and clouded the clarity of my commitments. For true alignment with my goals, it was essential to maintain a heartfelt commitment, unswayed by external noise and superficial encounters.

While I couldn’t compel a cosmic affordance to manifest at will, I could cultivate the environment in which I might receive it by selectively accepting invitations to conversations and events that signaled some degree of intuitive resonance.

To strengthen my intuitive resonance, I incorporated tarot into my routine. Not as a divinatory tool, but as a rich system of symbolism to hone the connection between my body-intelligence and mind-intelligence. Eschewing traditional interpretations of the cards, I focused instead on developing a personally meaningful symbolic vocabulary.

Each tarot card presents a visual and conceptual stimulus laden with symbols. Body-intelligence interacts with these symbols through sensory experiences — feeling and reacting to the imagery — and mind-intelligence processes these experiences through pattern recognition and linguistic analysis.

This dual engagement helps to attain a better understanding of the card’s significance in the context of personal experiences and challenges.

For instance, the symbolism on the Fool card might spark a sense of excitement or the anticipation of embarking on a new adventure — an instinctual reaction from body-intelligence. This could prompt mind-intelligence to explore new opportunities or plan a trip.

The imagery of the Empress may stir feelings of comfort and nurturing (body-intelligence), which could inspire practices for cultivating an environment that supports the growth of new projects and ideas (mind-intelligence).

The Justice card may evoke a bodily sense of equilibrium — a grounded feeling of symmetry — or, conversely, a visceral unease in response to imbalance or perceived injustice. This reaction might then prompt reflection on fairness and integrity, guiding conscious decisions that align with one’s personal and professional values.

I supported this reflective practice with a daily routine of yoga and qigong that contributed to more mindful awareness and a deeper inner alignment. Through this integrated approach, I refined my ability to recognize and interpret cosmic affordances while sharpening my sensory and cognitive capacities.

I chose tarot as my medium, but this method could be adapted for any symbolic system that facilitates a dialogue between sensory experience and intellectual insight, such as the I Ching (Book of Changes) or mythology and folklore.

COSMIC AFFORDANCE + A+B+C = NEUROCHEMICAL REWARD

In examining my daily routines and habits, I noticed a recurring pattern: the actions of my morning routine often dictated the rhythm of my entire day.

At the beginning of the restructuring, I habitually reached for my phone to scroll through TikTok before even getting out of bed. Formed in response to worsening burnout and a depleted dopamine baseline, this habit provided an easy hit of “false” dopamine to kickstart my day.

While occasionally educational, this ritual contributed little to my personal growth or productivity. Even more troubling was the gradual nibbling away of my attention span and cognitive function. Too often, I’d spend excessive time scrolling, leaving me rushing through the rest of my morning and setting a frenetic tone for the rest of the day.

Recognizing this as an undesired-state, I set the intention to shift toward a more mindful start to my mornings. Once the heartfelt intention was in place, I didn’t have to wait too long for the cosmic affordance to show up.

While taking a train to upstate New York, I came across a recommended YouTube video: Riding a train until I understand hyperspheres. So while on one journey, I watched a video about another.

The content was mathematics stratospherically above my level. Yet, the warm nudge of a cosmic affordance was unmistakably present (the creator even used bees to illustrate a point). Despite the struggle to grasp the concepts, waiting for a clue or a cosmic wink, I watched the entire video. And then, at the end, in an ad by the video’s sponsor: “Brilliant makes it easy to build a daily habit of learning.”

The universe had subjected me to 22 minutes of utter perplexity to make its point. “Here you go,” it seemed to say. “Time to switch tracks from quick dopamine fixes to something a little more lasting.”

I’d rarely connected with the traditional lecture-based teaching that was prevalent in my educational experience before design school. Brilliant’s interactive learning format and compact lessons were far more engaging, which did, in fact, make the app easier to include in my routine.

In the container for creative transformation, I first acknowledged the reason for my TikTok habit (dopamine release) by continuing to allow morning screen time (condition A). However, I timeboxed this activity (condition B) and made sure it was followed by at least one completed lesson on Brilliant (condition C).

As time passed within this transformation container, my reliance on TikTok lessened, creating space for microlearning to become a staple in my morning routine.

At first, I revisited the easy stuff — Foundational Math — to establish consistency, then gradually progressed to more complex topics — like Quantum Physics.

Just as quantum states exist in superposition — holding simultaneous potentialities until observed — my cognitive and behavioral states were shifting with each new subject I engaged in, transitioning from passive consumption to active learning. Each step a deliberate collapse of old patterns into new, more constructive habits.

Eventually, I observed a distinct shift: my brain began to favor the “true” dopamine rewards derived from completing tasks and achieving tangible learning goals over the “false” dopamine spiked by the addictive and repetitive interactions on TikTok. I felt more motivated and accomplished after engaging with the educational content in contrast to the restless dissatisfaction often left by prolonged scrolling sessions.

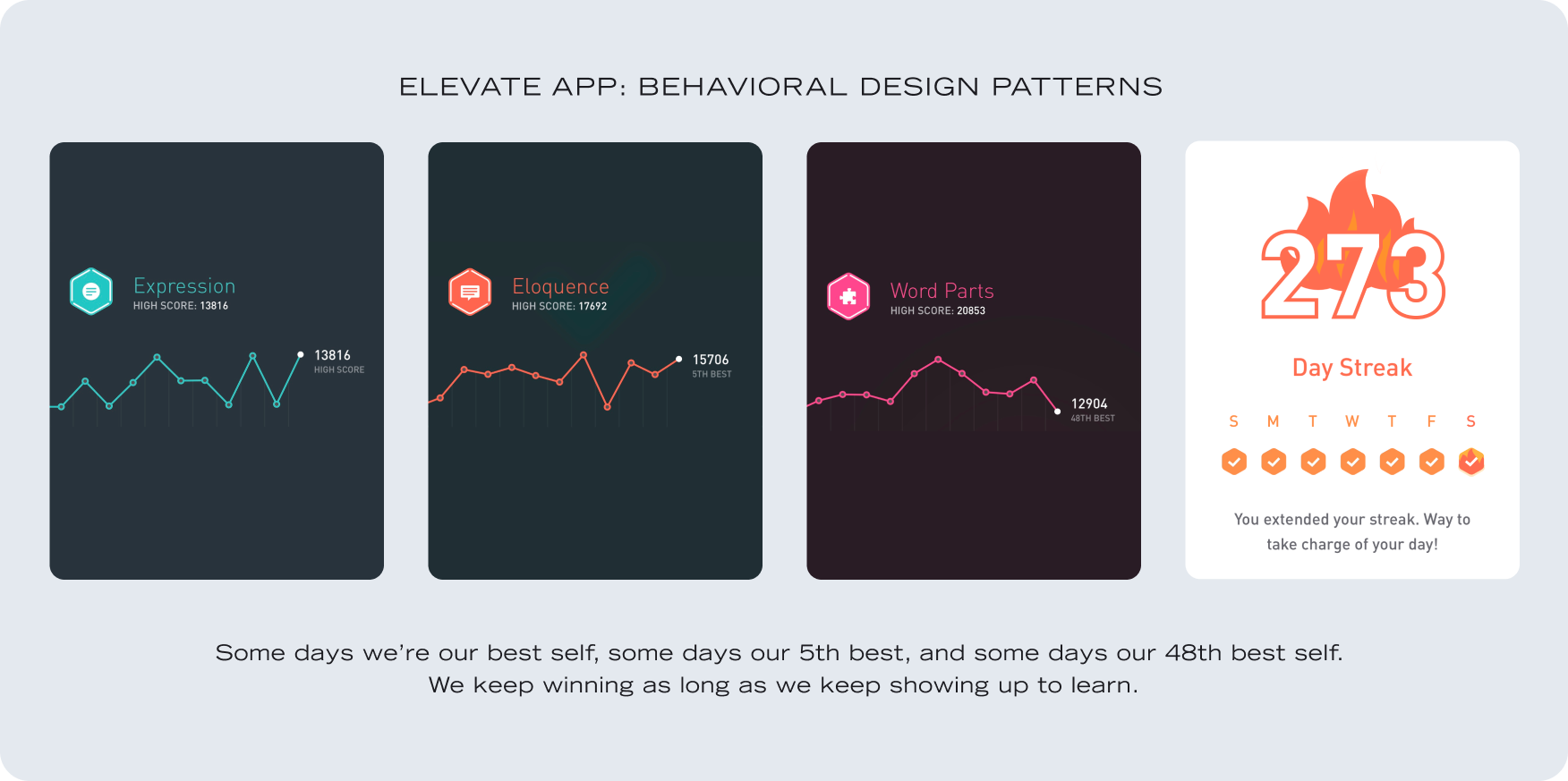

With this new baseline state in place, I introduced another microlearning app, Elevate, to fully phase out TikTok. Elevate’s quick “brain workouts” are aimed at enhancing essential mind-intelligence skills like vocabulary, quantitative reasoning, and memory recall.

Additionally, the app’s behavioral design patterns helped reinforce my new habit by tracking personal progress rather than fostering competition with others, while its streak counter encouraged consistent engagement.

Around this time, a trend on TikTok centered on repeating positive daily affirmations to “manifest” changes in identity. Interestingly, neuroscience supports this practice, showing that repeating positive affirmations can rewire neural pathways by engaging the brain’s reward systems, forming new connections, and reinforcing positive thought patterns.

By choosing active learning over passive content consumption each day, I was engaging in self-directed neuroplasticity while consciously affirming a belief that was vital for my recovery: my only competition is my past self.

Daily progress would vary — some days would bring significant breakthroughs while others might offer modest improvement — but every day held value as long as I engaged and learned.

With my desired-state established, I shifted the tone of my mornings — and consequently, the rhythm of my entire day — toward a commitment to continuous growth and learning.

I then applied the transformation framework to other areas of my daily life, from improving time management to refining my diet and skincare regimen — each guided by a cosmic affordance and adjusted within its own creative transformation container.

MORNING PAGES

While my cognitive abilities were consistently sharpened by my new microlearning routine, I continued to struggle with emotional-mental clarity.

For too long, I’d relied on mind-intelligence to untangle emotional complexities — a task it’s not built for. Mind-intelligence thrives on analyzing, researching, and playing with ideas, but emotions are too fluid and nebulous for a logical lens. They have to be felt to be processed.

I understood that the commonly recommended solution for emotional clarity — and a more fitting role for mind-intelligence in this context — was journaling. But traditional methods, like using structured prompts or recounting my day each night, felt rigid and unhelpful. I found little relief in the practice and couldn’t stick to it.

So, I set the intention to be guided toward a meaningful way of clearing the emotions that had taken up residence in my mind — a place they didn’t belong.

A few days later, after my mom decided to clear out the storage room, she left a box in my room filled with things from my past (before I began my professional life). I wasn’t exactly eager to sift through it and unearth the Pandora’s box of memories and emotions it held. But sitting right on top was a journal I’d sporadically kept when I was 12, with a page marked with a library card.

The writing was mainly expositing the plot of some Harry Potter fanfiction I was planning to write, but between the narrative musings, I’d woven in random thoughts and observations from my day. As I read more, I was unexpectedly charmed by my 12-year-old self’s honesty and carefreeness — she was unapologetically herself, writing as though no one, not even her future self, would ever read these words.

I’d left my fanfiction-writing days behind at 14, but the meaningful coincidence naturally intrigued me. The journal alone didn’t seem to hold the answer, but the library card was another clue. So I decided to visit the local library — the very same one where I’d gotten that card 22 years ago.

Without a specific goal in mind, I wandered through the stacks, eventually finding myself in the self-help section — a genre I’d deliberately avoided during my recovery to stay self-directed. I was about to move on but a gut feeling pulled me back. Scanning the spines, nothing stood out at first, but then I noticed a book cover in red-and-gold Gryffindor colors: The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron.

Instantly, I recalled a vocal exercise Fran had taught me during our sessions: a siren-like low-high-low cycling through the name “Julia” (drawn out as “Ju-OOO-li-aaaaaaa” — it was an exercise I’d only attempt when no one was within earshot). A pointed cosmic nudge.

The Artist’s Way is a creative recovery program that weaves together self-reflection, spirituality, and daily creative exercises to help unlock blocked creativity.

The exercise that resonated with me was called Morning Pages: writing three (I allowed myself flexibility with the number) pages of stream-of-consciousness thoughts, longhand, first thing in the morning. The goal isn’t to produce something profound (though insights naturally emerge) but to clear mental clutter, making space for creativity to flow.

This exercise serves as a “brain drain,” processing whatever’s lingering — petty grievances, anxieties, half-formed ideas — so they don’t block the day ahead. There’s no narrative structure, just thoughts interwoven as they arise (much like my journaling style at age 12).

The focus is on consistency over perfection, with the added guideline to avoid rereading the pages (for at least several weeks, the book suggests) to write without the pressure of judgment or expectation.

This practice allowed me to involve mind-intelligence appropriately in processing felt emotions through language, which contributed to greater clarity. I integrated Morning Pages into my routine while setting aside the other prescribed exercises in the book; following them without intuitive resonance would have defined the path.

With a desired foundation gradually rebuilt and mental clarity steadily being restored, I sensed the time was coming to return to design.

RETURNING

For a long time, burnout had made design synonymous with frustration and force, and I needed a way to detach from that negative association.

I took a months-long break, avoiding it entirely. If an idea came to me, I noted it down, but made a conscious decision to step away from active design work. It was during this hiatus that I’d focused on transforming my daily habits so that when I returned to design, I’d have a supportive structure already in place to sustain my creative exploration.

By now, I’d transformed several habits and had learned to trust that once intention and focus were set in a particular area, meaningful guidance would eventually show up. This unpredictable nature of cosmic affordances taught me a valuable lesson in discipline.

For a few years now, for personal and professional projects, I’d worked in intense bursts followed by dejected periods of stagnation. When a spark of inspiration would hit, I’d drop everything to ride that wave. But when it dried up, I’d be left floundering, unsure when — or if — it would come back. As burnout worsened, that spark became increasingly rare.

So I set the intention to cultivate a consistent creative flow rather than continue relying on cyclical intensity. In the interim, I focused on building discipline with my current transformation containers.

These gaps in between moments of cosmic inspiration became vital, ensuring that any changes I made were mindful, intentional, and lasting through dedicated practice.

*

One day, I woke up from an afternoon nap to the scent of simmering plums wafting through the house. Homemade plum jam was a staple of my childhood, and that scent swiftly took me back to carefree summer days spent playing, exploring, and causing a little mischief. As I was daydreaming about that long-ago life, my attention landed on the box of memories still sitting untouched in the corner of the room. Already in the throes of nostalgia, I decided to finally go through it.

Hidden under old photos and birthday cards, I found a book I’d bought years ago but never got around to reading: The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard — a philosophical exploration of memories and daydreams.

Feeling a familiar cosmic energy, I abandoned my rummaging in favor of curling up with the book while indulging in freshly baked bread and homemade plum jam.

As I read the first chapter, a passage gripped me:

“Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home and, by recalling these memories, we add to our store of dreams; we are never real historians, but always near poets, and our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost.” (p. 6)

I kept returning to that phrase — a poetry that was lost. I couldn’t move past it.

I dug back into my own box of memories and fished out an old hard drive from my days at Parsons. The project I was looking for was one I’d called Memoryplace.

Memories have always fascinated me. When I moved to a new country at age 10, besides a few personal mementos the only real possessions I’d brought with me were my memories. Speaking my mother tongue, Urdu, seemed to conjure memories vividly, but it was scent that really took me back. Plum jam, cardamom, pomegranate. Night-blooming jasmine and rose water. A poetry that was lost.

In 6th grade, I learned why. Scent is the strongest trigger for recalling memories because it activates the brain’s limbic system, which governs emotions and long-term memory. Unlike other senses that are processed through the neocortex, olfaction is unique in its direct pathway to the emotional center.

After discovering this, I’d initiated a long-term experiment using different perfumes each school year as anchors to recall memories. This led to an interest in making scented candles as a way to capture meaningful moments. An expression of a poetry that was lost.

Memoryplace had also once been a deeply personal project where I explored a method of memory recall by embedding memories into objects placed in sketched structures of houses — sketches being an architect’s store of memory.

Back then, it was a one-dimensional exploration, but as I revisited it, I began rethinking the concept. If scent is the strongest connection between body-intelligence and mind-intelligence, how might this experience translate across other faculties?

In my design work, accessibility had primarily focused on translating visual interfaces for sight-impaired users. What might accessibility look like across different senses? For someone without a sense of smell, how might I translate scent-triggered memory recall through color or sound?

While researching this line of thought, I came across a study about how the brains of congenitally blind individuals perceive visual concepts.

The study revealed that for sighted people, color is processed straightforwardly — see red, think “red.” But for non-sighted people, mentioning a color activates the regions of the brain responsible for abstract thought.

“The way they learn about red is the way [a sighted person] learn[s] about quarks, or about concepts like justice or virtue,” explained Alfonso Caramazza, the study’s co-author.

This reminded me of a challenge our design team once faced at Watermark. One of our designers was tasked with naming accessible color palette themes for ePortfolio templates. At the time, our best solution was to give practical examples: a palette with predominantly blue tones, for instance, might suit medical contexts.

But considering the research study, our approach didn’t fully align with our intentions.

Accessibility isn’t just about providing information — it’s about creating an experience that’s equally meaningful for everyone. What if we’d approached that challenge from a more poetic, abstract lens, aligning more closely with how non-sighted users conceptualize colors?

As I was lost in these reflections, something clicked: my creative excitement was back, and showing me clearly what fuels my passion in my work — creative reciprocity between professional projects and personal explorations.

The frustration I’d come to associate with design was rooted in losing touch with what drew me to it in the first place: the joy of meaningful creative discovery. Over time, I’d grown too focused on outcomes and achievements, gradually losing the imaginative richness that once sustained my creativity.

Our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost.

That’s what this entire journey was revealing — that design is more than just a job for me; it’s integral to who I am.

It was as if I’d scattered these breadcrumbs for myself over the years. As if I’d somehow understood, though I didn’t know, that one day I would need to find my way back. And I was exactly where I needed to be to pick up that trail.

Plum jam daydreams and Memoryplace — points of connection in a boundless place.

After all, what is memory but compressed time and space?

*

I was thrilled to feel a creative spark again after what felt like an eternity. But from my experiences with other transformation containers, I knew that transitioning from intensity-driven bursts of creativity to a steady flow wouldn’t happen overnight.

In the beginning, I held on to my preceding-state condition, only engaging in design when inspiration struck and intuition aligned. When it didn’t, I consciously let it be.

For months, I cycled between inspiration and stagnation, setting a new intention for anything that might help bridge the gap. Then at the dentist’s office one day, I overheard a patient telling the receptionist, “If you want to run a marathon, learn to paint.”

That sentence echoed in my mind for the rest of the day.

Painting used to be a favorite hobby, but like design in recent years, I’d grown impatient with the process and overly fixated on the result.

The next day I met a friend for a picnic in the park. She brought along a paint-by-numbers kit for us to work on while we chatted. And just like that, the answer appeared.

I’d never thought much of paint-by-numbers, dismissing them as “uninspiring.” But the methodical, consistent work without the expectation of “achieving” anything grand was exactly the discipline I needed to rebuild.

When we started our sessions, Fran had given me a book: The Talent Code by Daniel Coyle. The book explores the science behind talent development, showing how practicing adjacent skills often enhances the primary skill being mastered.

The book gives an example of Brazilian soccer players who practice by playing futsal, a high-intensity version of soccer played on smaller, concrete courts. The game’s constraints of limited space, high pressure, and a smaller, heavier ball force players to sharpen their decision-making and develop refined ball control — skills that translate directly to traditional soccer.

In a similar vein, paint-by-numbers provided me with a low-pressure environment to rebuild my creative discipline with a relaxed, almost meditative re-engagement. Both activities support skill development, just on opposing ends of the spectrum — intensity vs. ease, high pressure vs. low — each fostering a return to creative flow in its own way.

When I felt inspired, I worked on research and design for Memoryplace. In between, I switched to paint-by-numbers, devoting consistent time to each practice.

I also noticed a distinction between my personal projects and professional work that I hadn’t considered before: for my personal, inspired projects, I’d always chosen Figma, while all the teams I’d worked with professionally used Sketch. In my experience, Figma’s strong design community made it a more inviting world for designing.

Design worlds, as Donald Schön once described, are “environments entered into and inhabited by designers when designing. They contain particular configurations of things, relations and qualities, and they act as holding environments for design knowledge.” (Designing: Rules, Types, and Worlds)

Sketch was the design world that — through no fault of its own — had come to hold my resigned frustration. To signal a fresh start, I committed to Figma as my design homeworld.

This shift also translated the paint-by-numbers habit-building process to active design work. Between moments of inspired work, I systematically transferred years of professional work from Sketch into Figma — reorganizing and refamiliarizing myself with the material in the process.

When I had rediscovered Memoryplace, I’d also unearthed a collection of mini mobile games I’d worked on during my Parsons days. These games were a creative escape that sometimes led to unexpected sparks of inspiration.

I brought them back into my design world by making them a regular part of my process.

With this blend of inspired work, disciplined practice, and playful creativity, my return to design was fully realized.

*

In my journey of personal development, because of the resource tradeoffs I committed to (leaving the job and the apartment), I was able to leave time as an open-ended variable. This flexibility allowed me to experiment with my framework in ways that aren’t always possible in more structured, professional settings.

But even in those contexts, this approach can be adopted: by letting inspiration and cosmic affordances guide major breakthroughs while committing to smaller, strategic initiatives in the interim. This helps avoid the trap of forcing premature actions and selecting outcomes that misalign with our true intentions.

Another vital aspect of this process was a demonstrated commitment to the desire for change. Sartre once said, “Whenever man chooses his commitment and his project in a totally sincere and lucid way, it is impossible for him to prefer another.”

Finding that lucid commitment requires tuning into our true expression and aligning with the outcome that resonates most deeply, allowing the authentic path to unfold naturally rather than forcing it through logic alone.

Habits, behaviors, and self-beliefs — those grooves in the brain dug repeatedly over years — aren’t easily changed. But with time and consistent practice, my many little transformation containers built up a stable home for my creative flow.

•

III.

I could have logically viewed and dismissed as “random” the series of “coincidences” that gave me the confidence to begin this self-experiment that transformed my life. But maybe what scientific theory terms as “random” behavior is a function of nature that exists to remind us that we aren’t purely rational beings living in a purely rational world. “Randomness,” then, is how we refer to the underlying cosmic pattern of the universe because it’s indecipherable through our intellect alone.

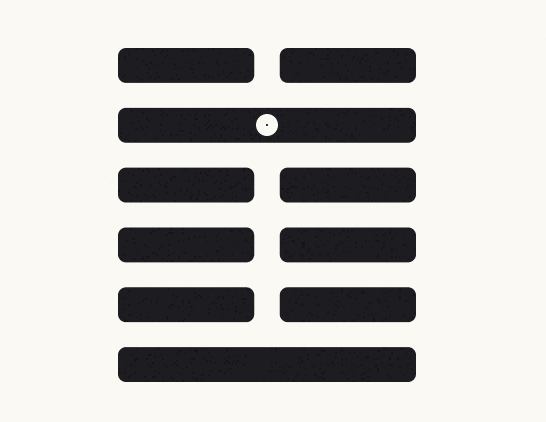

The 3,000-year-old book of philosophy and divination, the I Ching, explicates the changing flow of life through a system of hexagrams that represent different possibilities and states of being. It presents an underlying principle through its themes: the path knows you’re coming.

In quantum physics, the concept of superposition suggests that all possible outcomes of a quantum event exist simultaneously, forming a web of potential realities. These outcomes aren’t isolated; they’re interlinked in possibility. When an observation or measurement is made, the superposition collapses into a single, seemingly “random” outcome.

Similarly, I see cosmic affordances as intuitive cues within a field of possibilities and potentialities — ones that guide us toward a specific outcome that resonates with our internal experiences and intentions.

It’s interesting (because language, though a faculty of mind-intelligence, is fluid in interpretation) that what’s called a “gut feeling” in English is known in Spanish as a “heart feeling” (corazonada). And what we phrase as “making a decision” translates as “taking a decision.”

The path, the possibility within the web of possibilities, already exists. We don’t carve it out; we choose to take it. Then is it truly such a fanciful notion that this path, already existing and entangled with our eventual choice, anticipates and aligns with our decision to take it? That it signals its existence to us through personal significance — a cosmic affordance uniquely recognizable to each of us? What others might dismiss as mere coincidence could be, for us, a meaningfully unfolding pattern of prescience.

The journey, then, isn’t about arriving at predetermined outcomes; it’s about learning to dance with the universe — attuning to the rhythm of intuitive resonance and co-creating the path with each step, meeting it as it meets us.

In the words of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: “What makes the desert beautiful is that somewhere it hides a well.”

•

The title of this exploration comes from the I Ching’s hexagram 3: Chun, translated as “Difficulty at the Beginning.” Chun depicts a blade of grass struggling through dirt and rocks as it rises from the soil into sunlight. This hexagram symbolizes patience and perseverance, and advises that “difficulty at the beginning brings supreme success.”